A perfect storm is forming around the Malaysian ringgit, as its value remains at risk from a protracted economic slump aggravated by a domestic political scandal and the prospect of rising US interest rates.

But the distress does not stop there, as a currency sell-off in Malaysia could have a contagious financial spillover on neighbouring economies, sparking capital outflows and compounding financial volatility.

The value of the ringgit has nosedived dramatically over the past two years, along with investors' confidence in the government of Prime Minister Najib Razak. Mr Najib has been fighting tooth-and-nail to block any serious domestic investigations of the heavily indebted 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), which is being investigated in six other countries for dubious investments and opaque financial transactions.

Malaysia is particularly vulnerable to positioning adjustments because of high foreign holdings of domestic debt, relatively low foreign reserves, and the recent tightening of regulations on the offshore foreign exchange market, according to Credit Suisse economist Michael Wan.

As of November 2016, foreign holdings in Malaysian government bonds were 48.4%, valued at US$40 billion, according to Credit Suisse. That is considerably higher than in other Asian counterparts such as Thailand (14.5%, $17 billion), South Korea (14%, $62 billion), and Indonesia (37%, $49 billion).

Simply put, substantial foreign holdings in Malaysian government bonds represent a high risk of capital outflows when investors shift their portfolio positions from emerging markets to their developed counterparts.

That risk is rising as Donald Trump prepares to assume the US presidency with his vow to "make America great again" through fiscal stimulus measures such as tax cuts and infrastructure spending. Such policies have fuelled market expectations of higher inflationary pressure and thus more interest-rate increases by the US Federal Reserve.

"The sharp fall in Malaysia's ringgit echoes a general reassessment of portfolio allocations by international investors, and domestic political and policy uncertainties following how the [Malaysian] central bank reinforced existing rules to limit access to offshore trading of the currency," said Moody's Investors Service, an international credit rating agency, in a recent report.

The ringgit, which fell by 4.3% against the dollar last year following an 18.5% decline in 2015, has not posted an annual gain since 2012, according to Bloomberg. At 4.48 per dollar, the ringgit has touched its lowest level since the Asian financial crisis in 1998 and was Asia's worst-performing currency for emerging markets in 2016.

BEARISH OUTLOOK

Rainy-day conditions are likely to be prolonged for Southeast Asia's fourth largest economy, in the view of Jitipol Puksamatanan, global markets strategist at Krungthai Bank. He is convinced that Malaysia's economic fundamentals are among the weakest for emerging Asian economies because of low foreign reserves, weak public investment resulting from ebbing fiscal revenue, and a bearish outlook for domestic politics.

Compounding Malaysia's susceptibility to capital flight are prolonged low oil prices that have resulted in trade deficits, while Mr Trump's trade protectionism could cast shadows over Malaysia's export-dependent economy, as 8.4% of its shipments go to the US, he said.

"If the ringgit's value experiences a heavy speculative attack, then there is no sufficient buffer to defend against currency depreciation," Dr Jitipol told Asia Focus.

He pointed out that ringgit's year-to-date value versus the greenback reflects lukewarm investor confidence. It also remains vulnerable to high fluctuation, with one-month volatility recorded at 11.3%.

"If the ringgit's value weakens to 5 versus the dollar, [Malaysia's central bank] could impose capital controls," said Dr Jitipol.

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) in November requested foreign banks to stop trading ringgit in the offshore non-deliverable forwards market. Prior to that, it also confirmed that it had intervened in the market to defend the ringgit. These developments have spurred concerns over the central bank's foreign-exchange policies and raised the spectre of capital controls.

BNM did not respond to an email request by Asia Focus to comment on the ringgit's decline and strategy to mitigate capital flight.

Malaysia last imposed capital controls two decades ago during the 1997-98 crisis by fixing the exchange rate and requiring the currency to be held for at least a year after the sale of Malaysian securities or assets in the country. Mahathir Mohamad, the prime minister at the time, was widely criticised for what investors deemed an extreme measure, but the move was widely viewed as a major contributor to a fairly rapid and impressive economic recovery.

Some analysts, however, believe the current pessimism is overdone. Among them is Peter Chia, a foreign-exchange strategist at United Overseas Bank (UOB), who says that not all foreign-held assets in Malaysia are at risk of any immediate sell-off. Based on distribution of foreign holdings in government bonds as of the third quarter of 2016, most represent "real money" or long-term holders, namely asset managers (38%), central banks and governments (28%), pension funds (15%), banks (15%) and others (5%).

Malaysia's underlying fundamentals and positive demographics remain intact, adds UOB Malaysia economist Julia Goh. Such optimism is reflected in how Malaysia's pursuit of fiscal reform measures has helped to avert negative effects from weak oil prices.

As well, she said, the growth potential linked to large infrastructure projects such as the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore high-speed rail line cannot be underestimated.

Against ever-challenging global and domestic backdrops, BNM is expected to maintain its 3% policy interest rate throughout this year as economic growth and inflation are picking up moderately, said Mr Wan of Credit Suisse. His bank forecasts the ringgit to trade at 4.55 against the dollar over the next 12 months.

Although Malaysia's current account surplus this year is projected to improve from 1.9% to 2.3% of GDP, there remains a concern over ringgit volatility because of possible Fed action and uncertainty over the Malaysian central bank's forex policies, he said.

"Overall, the macroeconomic outlook should improve from a weak 2016, but foreign-exchange risk is the key constraint on us turning more positive on Malaysia," he stressed.

AILING TIGER

Dubbed one of the Asian tiger cub economies during the economic boom of the 1980s, Malaysia is seeing its economic success story, propelled by industrialisation and exports, fading as fiscal constraints limit growth. As a net oil exporter, Malaysia has seen a gradual decline in revenue on the back of low crude oil prices.

The government will be constrained in its response to a slowdown. Amid the need for fiscal consolidation, it targets a narrower budget deficit of 3% of GDP for 2017, against an estimated 3.2% in 2016, although the recent recovery in oil prices, if sustained, could help at the margin, said HSBC economist Su Sian Lim.

The budget deficit remains susceptible to swings in oil prices, although the 6% goods and services tax (GST) introduced in April 2015 has helped to mitigate some of the downside risks on this front, she said.

"Malaysia's financial support for its reform initiatives, which aim to promote investment and inclusive growth, is capped by the government's pursuit of fiscal consolidation against a backdrop of slowing revenues," said the Moody's report.

Casting shadows over fragile domestic demand is the rising unemployment rate, standing at a multi-year high of 3.6% in September, and weak private consumption growth curbed by household debt equivalent to nearly 90% of GDP, said Ms Lim.

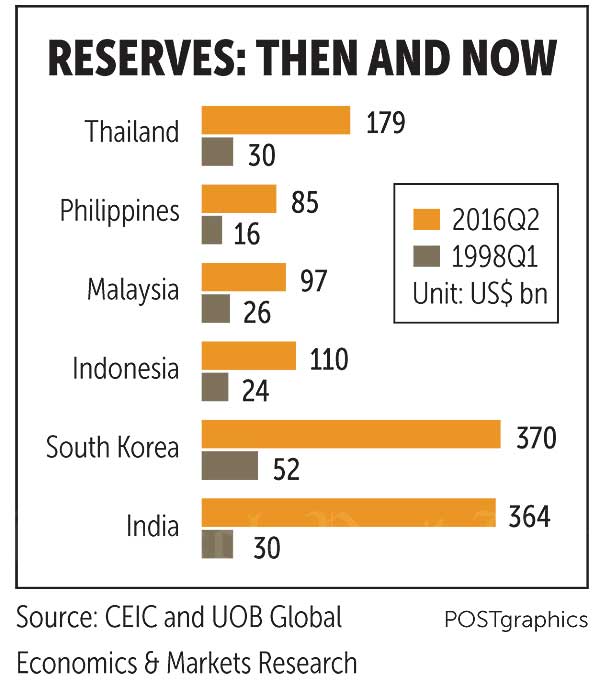

Coverage of short-term external debt from foreign reserves, meanwhile, is the lowest in the region, said Ms Goh.

The level of Malaysian reserves is equivalent to 1.2 times short-term external debt and 8.3 months of retained imports, she said. As a rule of thumb for reserve adequacy, the overall stock of reserves should cover at least 3-5 months of import payments and 1.0 times short-term external debt.

The overall external debt profile is, however, largely tilted toward medium- to long-term external debt, at $128 billion or 61%, with $81 billion or 39% attributed to short-term debt, said Ms Goh.

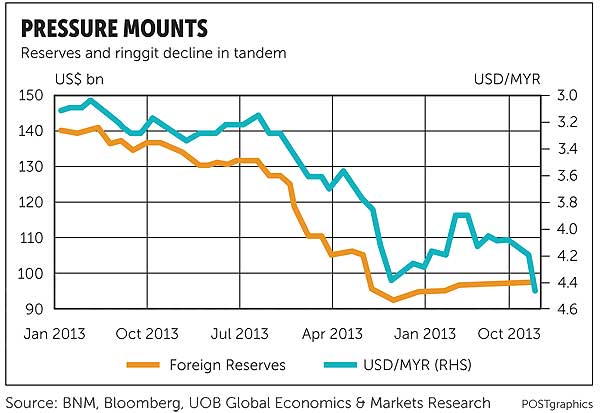

Malaysia's foreign reserves amounted to $94.6 billion at the end of 2016, compared with $95.3 billion a year earlier and $116 billion in 2014. They peaked at $141 billion in mid-2013.

POSSIBLE SPILLOVER

Given the predicament facing Malaysia, questions arise about whether neighbouring countries would face a spillover effect, potentially limiting regional growth.

Krungthai Bank's Dr Jitipol allays concerns over a possible decline in trade and investment stemming from Malaysia. He says regional economies face greater risks from China's economic slowdown and Mr Trump's trade protectionist policy. However, Malaysian outbound investment could be affected to a certain degree by the country's weak economic growth outlook, he said.

If Mr Trump takes steps that trigger a trade war between the US and China, it would be negative for the Asean region as a whole given the high trade links to both giant economies, UOB's Ms Goh said.

Singapore was Malaysia's largest export market between January and November last year, with export value of 103.5 billion ringgit ($23.2 billion), according to the Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation. It was followed in order by China, the US, Japan and Thailand ($8.9 billion).

But the ringgit rout could induce financial volatility across the region as investors tend to link investments in emerging Asian economies into the same portfolio, he said. Regional currencies could depreciate sharply following an emerging market sell-off.

"Investors will try to avoid betting on unknown factors as Malaysian politics might not turn out to be as expected," said Dr Jitipol.

While pointing out that every country's economic structure is different, Mr Wan of Credit Suisse offers a word of advice for Asian economies to build up capital buffers in order to cushion against financial volatility.

The valuable lesson learned from Malaysia's downward spiral is how transparency in governance is vital in shoring up investment sentiment and sustaining economic growth momentum, noted Dr Jitipol.

Substantial foreign holdings in local debt instruments are a double-edged sword. On the plus side, they provide supplemental liquidity, but there is a downside risk of excessive capital outflows, he said.