Due to unscrupulous state officials and greedy real estate developers exploiting legal loopholes, many high-rises manage to spring up in narrow sois in Bangkok, posing environmental problems and safety concerns.

A source who has been working in the construction industry for decades told the Bangkok Post that the 1979 Building Control Act has been exploited in prime areas in Bangkok.

Under the act, the height of buildings is capped at 23 metres -- about 7-8 storeys -- if the road or soil leading to the construction location is smaller than 10 metres in width, or about two traffic lanes.

The rule, however, prohibits developers from being able to recoup their costs as building low-rise condominiums in central business areas in the city is not economical.

This has led some developers to bend the rules.

"Most of these projects are on Sukhumvit Road, in the Ploenchit, Ekkamai and Thong Lor areas, which are all prime locations where land prices have been skyrocketing," he said.

No room to manoeuvre: Firefighters struggle to control a blaze in a small soi in Bangkok’s Yaowarat in February. (Photo by Pornprom Satrabhaya)

The average price of a condominium unit in these areas is 200,000 baht per square metre.

"So, the larger the number of units each condominium project has, the higher the profits it will gain," said the source.

"One of the common tactics used to seek approval for a residential high-rise project is to widen the soi in front of the project by donating land back to the city so the street in front of the property becomes wider than 10 metres and thus the rule is circumvented," said the source.

Another popular trick is splitting a large residential building project into a cluster of smaller ones to avoid the construction law.

Under the act, a building along a soi or road smaller than 10 metres in width can be no larger than 10,000 square metres in size.

CARRYING CAPACITY

There are sound ecological reasons behind these regulations.

"The law is written to make sure that the number of residents, resource use and waste in each soi match the carrying capacity of the space," said a high-ranking official at the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) who asked not to be named.

Carrying capacity is the number of people that an area can support without environmental degradation.

Taller and larger residences mean more people, more cars and more waste generated.

Water-logged: A flood along Sukhumvit Soi 39 last year. The infrastructure in small sois isn’t designed to accommodate water draining from high-rise buildings. (Photo by Varuth Hirunyatheb)

"You need to understand that infrastructure in small sois, including drainage pipes, isn't designed to accommodate the volume of water drained from a high-rise building," he said.

"More importantly, when there is a fire at a high-rise, it is impossible for a large fire engine to get to the building because the soi leading to it is way too small," he said.

This source said that the building control law should be amended to prevent exploitation.

"There should be a change to prevent developers from splitting a large project into smaller ones.

"The new law should count the usable space of all smaller buildings on the same premises as one project [if proved to actually be owned by the same developer]," he said.

However, the BMA has made no attempts to close these loopholes.

TOO BIG TO FAIL

The case of Aetas Hotel and Residence in Soi Ruamrudee 2 is a classic example of a high rise being built unlawfully in a small soi.

The case was first filed with the Administrative Court in 2008 by 24 residents accusing a number of BMA executives, including former Pathumwan district chief Surakiat Limcharoen and former Bangkok governor Apirak Kosayodhin, of negligence for approving the project.

The BMA was also accused of issuing a certificate exaggerating the width of the road to push the project through.

In February 2012, the Administrative Court ruled the BMA wrongly allowed the buildings to be built. Two years later, in December 2014, the Supreme Administrative Court ordered City Hall to knock down the buildings -- one 24 storeys tall and the other 18 storeys -- for violating the city's construction ordinance.

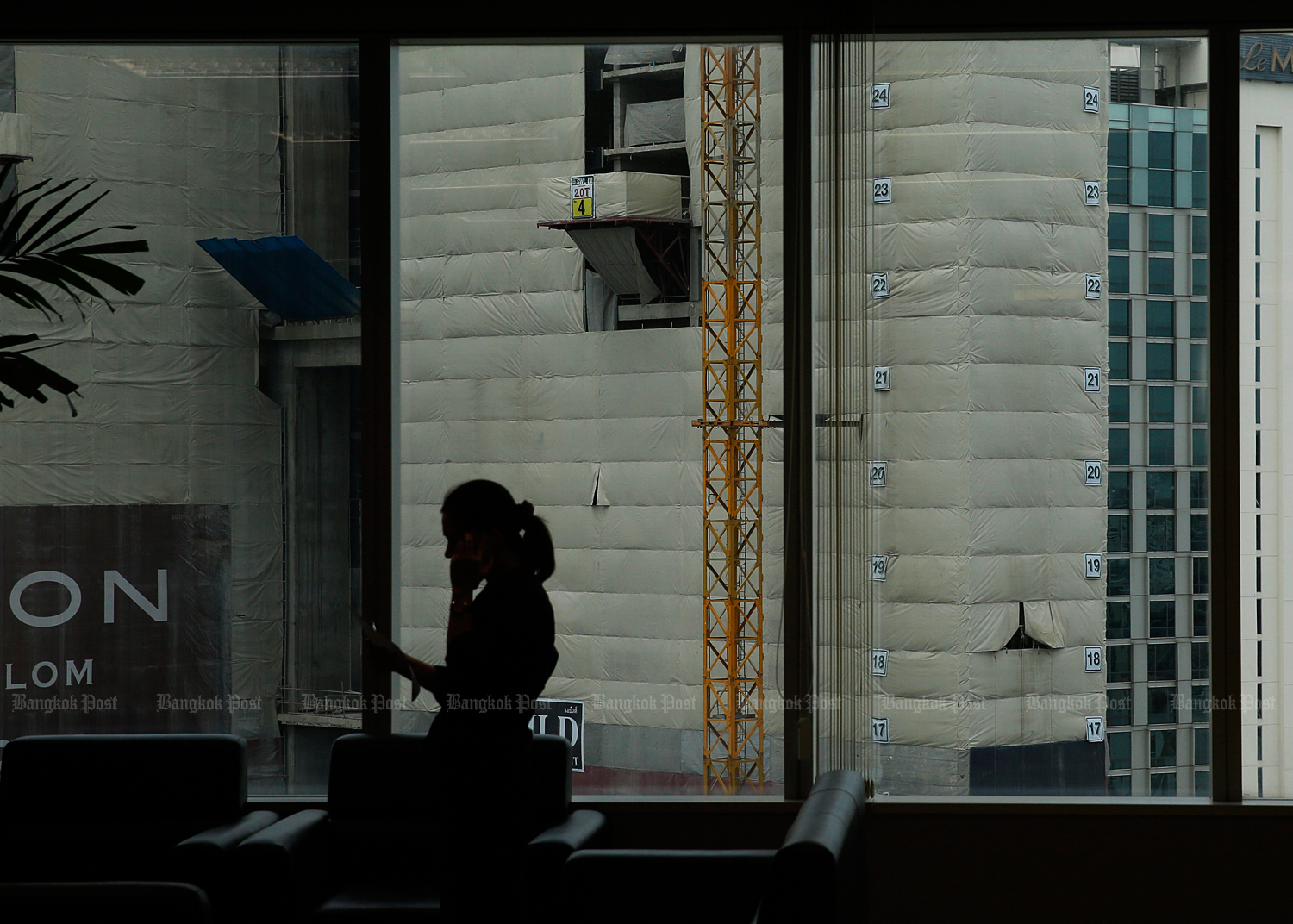

Valuable real estate: In Bangkok’s central business district including Sukhumvit and Sathon, high-rise buildings pepper even the smaller sois. (Photo by Pattarachai Preechapanich)

Despite the court ruling, no action has yet been taken and the buildings and their occupants remain.

The source admitted that it is "highly unlikely" that Aetas Hotel and Residence will be demolished as instructed by the court.

"BMA officials fear the legal repercussions [of carrying out the court order]. Any BMA official who orders the demolition of Aetas' buildings may end up facing a legal suit from an owner who insists they obtained documents from Pathumwan district office indicating the soi is 10 metres in width," said the BMA's source.

"This project is worth around 3 billion baht, so BMA officials are unwilling to act on the court order with any urgency due to fears of these legal repercussions landing them in hot water," said the source.

The bidding to find a contractor to demolish the building has been held unsuccessfully two times already, according to Pinit Arayasilpathorn, director of Pathumwan district.

A third effort, on March 21, saw two contractors make offers.

Talay Thai Thammachart quoted 161 million baht while Akkara Duangkaew asked for 162 million baht. The reference price was 172 million baht.

The quotes have been forwarded to the city clerk, although there are still many doubts among residents over whether the buildings will ever be demolished.

RESIDENTS STRIKE BACK

Residents living in small sois have started to fight back.

Among them is the local Phayathai Conservation Group.

The group comprises residents who have been fighting against unlawful high-rise projects in the area for a while now.

Formed nine years ago, the group now has 120 members who are residents of Soi Phaholyothin and has managed to have seven residential projects suspended already.

Reclaiming the sois: The Phayathai Conservation Group has managed to get seven residential projects suspended. (Photo by Tawatchai Kemgumnerd)

Known as Toong Phayathai Ground half a century ago, the district was originally filled with detached houses.

Three decades ago, government buildings sprang up in the area and, during the last decade, thanks to the construction of a BTS Skytrain station nearby, it has become a highly desirable plot for real estate development.

"The problem is that many high-rises have been built in small sois. However, the infrastructure and sizes of the sois have not been developed. So, residents now must endure chronic traffic congestion," said Norarit Komalarajun, 86, president of the club.

He said floods have also become a problem in the area because the sewage system and water drainage have not been upgraded or enlarged.

"Even though the area serves government offices, much of the pavement is too narrow for people to walk along comfortably."

Green space and flood retention zones have been replaced by large buildings which often leads to the roads becoming swamped with water.

Mr Norarit said many high-rises in small sois fail to provide set-back areas and green space as required by law.

The Building Control Act also requires developers of high-rise residential buildings to leave 30% of the land as vacant space to both retain floodwater and allow access to emergency service vehicles.

Prasert Lipwathana, 78, an adviser to the club, insists his group is not anti-development.

"But the laws must be enforced, or else real estate developers will continue to exploit loopholes," said Mr Prasert Lipwathana.