In a stage performance that just finished its run on Sunday, performers re-enacted scenes in which victims were hunted, beaten and strangled to death. In an art exhibition opening tomorrow, we'll see in paintings traces of atrocious scenes in the foreground while the surface is heavily smudged with paint, to the point of abstraction.

In another exhibition, an artist uses his own blood in recreating, in a half-tone pattern, a photograph featuring a student being hung and beaten. And in a new film, there's a scene showing students being made to lie down on the ground half-naked as armed policemen put feet on their faces.

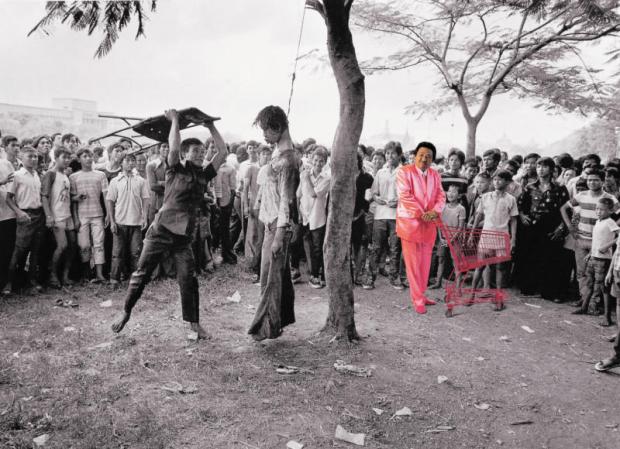

Tomorrow marks the 40th anniversary of the Oct 6, 1976, Thammasat massacre. It's almost a tradition to evoke the gruesome undertones of the event at this time of year, in news, in art, in seminars. In social media, ghastly black-and-white photographs by American photographer Neal Ulevich of student protesters being attacked and killed by Thai state forces and far-right paramilitaries have been circulating. A few universities are set to organise commemorative events, with speeches to be made and flowers to be laid.

Despite the 40 years that have elapsed, the event remains a taboo subject. Photos circulating are accompanied with vague captions while speeches are sure to touch only the surface of things, just like how this darkest chapter in Thai modern history has never been thoroughly elucidated in any official account.

Thai contemporary art, theatre and cinema echo that elusiveness, too, varying in degree of emphasis -- either referring the event in passing, observing it passively, layering it under other narratives, re-enacting the incidents through body movements, or provoking the viewers to think through art.

In Kosit Juntaratip's exhibition "Allergic Realities", in which he uses his blood as paint, the artist put the Oct 6 event in a bigger context, the scene of a student hung and beaten placed among other iconic shots of the world's historical atrocities, such as the Napalm Girl of Vietnam and the Tank Man of China.

In Anocha Suwichakornpong's latest film, Dao Khanong (By The Time It Gets Dark), the story is told of a director making a documentary about a former student activist of the October generation in the 1970s, featuring a scene with students lying face down, before the plot shifts away.

In other cases, the works are directed at this particular topic as a reminder, urging the audience to ponder this tragedy in which arguably more scores of protesters were beaten, shot, hung and burnt to death during protests against the return of military dictator Thanom Kittikachorn.

The stage performance that just finished its run is Fundamental, a movement-based show by B-Floor Theatre's Teerawat Mulvilai, which was inspired by Ulevich's image of a student hung under a tamarind tree. Soon after the premier earlier last month, Teerawat was informed that military officers would be dispatched to monitor his show.

"This show questions whether or not this country wants the truth," said Teerawat when asked why he constantly goes back to the Oct 6 event when creating many of his works. "There have been many similar incidents both before and after, but this particular event speaks best about the idea of justice in the way that, unlike other times, ordinary people are also involved in persecuting their fellow citizens."

For the most part, Fundamental is non-verbal; an ensemble of performers go from playing hunters to victims, and at one point, one is picked out and bullied before being attacked and strangled to the satisfaction and laughter of the rest of the cast.

Teerawat admitted that although it won't be soon before people can openly discuss the issue, he created the work because he's hopeful and that, in 20 years' time when maybe everything is different, he can face himself in good conscience that he did his responsibility as an artist.

"Our country is going nowhere because there's still this culture of impunity," said Teerawat. "Look at the Gwangju Uprising [in South Korea], for instance. The people fought the law, and finally those leaders responsible for the massacre had to face their punishment. Whereas for us, those responsible never had to go to jail. It's frightening how people encountered violence and yet are ready to forget all about it soon after."

This idea of being indifferent towards violence against fellow citizens brings to mind "The Pink Man", an ongoing art series initiated in the late 90s by renowned Thai photographer Manit Sriwanichpoom. One series, entitled Horror In Pink, shows his character the Pink Man, standing without emotion, photo-shopped onto Ulevich's horrendous photographs from 1976.

"Pink Man is a representative from this age who participates in laughing and enjoying that atrocity," said Manit. "My art is a means of not letting the event fade away, immortalising this chapter of history." Manit said it's an issue of history and memory -- only history of the royalty was recorded, while the fight of the people was never written down and taught in classrooms.

In the case of Chiang Mai-based artist Thasnai Sethaseree's latest exhibition, "What You Don't See Will Hurt You", which opens at Gallery Ver tomorrow, some of the works in the show respond directly to the massacre by literally and visually demonstrating the way in which the ugly truth is gradually obliterated.

Thasnai uses images related to the violent incident as a base of his canvases, but for viewers, there's no identifying what they actually are. That gruesome scenes are smudged over and over with bright paint echoes the state's constant attempt to make this episode of brutality fade into abstraction.

"It's because we never properly address it that this scar has persisted even to the present," said Thasnai. "I'm merely doing something that an ordinary citizen can do, and art is my way of communicating. It is not my hope that my art will bring about change; I just hope that it can help the audience see and think the way they never did before."