'I think they're just selling clothes here," said one of three girls, as they walked out of the narrow, circular corridor leading to an exhibition space at the Bangkok Arts and Culture Centre.

Just moments earlier, she had peeked into the gallery and, seeing only racks of army jackets embroidered with colourful motifs, decided to turn back.

What she had actually caught sight of wasn't a pop-up store or a fair event. It is an art installation, Changing Room, which examines the tensions between Buddhist and Muslim communities in Thailand's restive South.

Violence is vividly depicted in artist Jakkai Siributr's set of monumental installation works collectively titled "Displaced: The Politics Of Ethnicity And Religion In The Art Of Jakkai Siributr", which are on show until May 13 at BACC.

Nationalism and historical revisionism across the region are also elucidated, with pieces referencing consequences of the Buddhist-Muslim divide in Thailand and Myanmar. The show has been curated by Lola Ienzi.

For a very long time, Jakkai wasn't so preoccupied with the tumult that was boiling up in Thailand's southern provinces.

"Back then, I had little interest in history." The subject, as taught in Thai schools, is but a narrative, twisted to serve the powers that be, he said.

Instead, the artist was intensely focused on depicting Thai Buddhism in the way that he saw it: synthetic, a fabrication that had absorbed cultural and spiritual elements of various origins. In doing so, he gained international acclaim.

But as the violence culminated, Jakkai remembered his earlier trips to Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat and Songkhla provinces, where he had collected knowledge regarding local textile weaving and colouring techniques.

The difference between now and then is stark, he said.

"The region was so beautiful. It still is today, but nearly 20 years ago, it was very peaceful." Thus, Jakkai began to question what had changed and what could possibly have caused such mutation.

In 2014, he completed 78, a sombre tribute to the 78 victims of the 2004 Tak Bai incident. The art piece consists of steel and wooden scaffolding covered with dark veils -- the cryptic structure that resembles a tomb or a mass grave is shown in Thailand for the first time today after several stints at international galleries.

Stacked bamboo shelves, each carrying a traditional Islamic tunic, imitate the way victims were piled up in trucks that transported them.

On the day the incident took place, soldiers rounded up protesters who had gathered in front of the Tak Bai police station in Narathiwat province. Eventually, they were crammed into trucks and, at the end of a five-hour drive to a Pattani military camp, 78 civilians died of suffocation -- thus the work's title 78.

Although many viewers have likened the black, cubic space, adorned with golden motifs, to the Kaaba -- Islam's most sacred structure in Mecca -- Jakkai said he merely intended it to be a sacred space, a mausoleum of sorts.

Before its 10th anniversary, an uneasy silence surrounded the tragic event. During his research trips to the South, the artist encountered soldiers and officials who believed that the incident shouldn't be mentioned anymore. "It's past the compensation process -- there is no use in talking about it now -- it's better to leave this behind," they told him.

"I disagreed. On the contrary, it's important that people continue to bring it up because it's part of our history," Jakkai said.

The memorial he built for the victims is claustrophobic yet meditative. Numbers -- one to 78 -- are embroidered on each of the gowns, while victims' names are stitched on the black cloths' outer surface, along with brass decorations representing amulets, but that also happen to look like bullets.

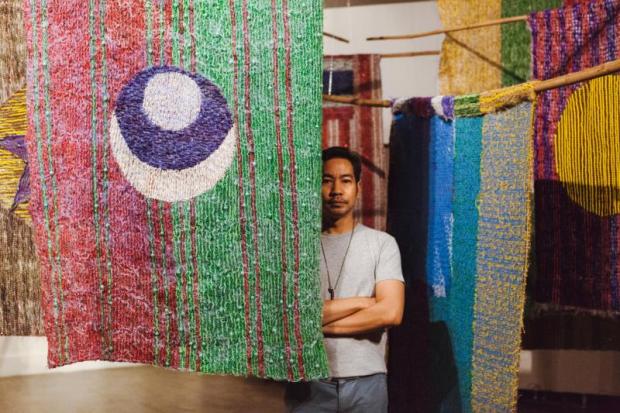

Displaced: The Politics Of Ethnicity And Religion In The Art Of Jakkai Siributr Courtesy of Jakkai Siributr

Before he began to work on the southern conflict, Jakkai did a towering amount of research. He dug up history books and talked to a wide array of local stakeholders.

Surprisingly, he found that many involved in the reconciliation process had little hope of attaining their goals by reaching out to older generations.

Owing to experience and trauma, they believe that adults are more prejudiced than children, being therefore less worthy of their efforts.

"Personally, I find this idea strange," the artist noted. "In order to move on and to reconcile, we should understand our history. We should all learn our history and acknowledge it -- not erase it."

78 aims to spur remembrance and recognition regarding an event past. But Jakkai's other piece addressing the southern insurgency -- Changing Room -- couldn't be more anchored in the present and takes centre stage in this exhibition.

With two rows of military jackets framing a mirror and table, on which are displayed traditional Malay-Muslim white hats, the artist conveys the many facets of reality in the Deep South.

Naive, childlike illustrations of Muslim families and Buddhist monks walking hand in hand are stitched on the camouflage fabric. So are rifles, buildings aflame and military checkpoints. The inner lining of the traditional caps is also covered in the same cloth, with embroideries of a similar fashion.

While Jakkai's art doesn't limit itself to textile supports, he had used this material predominantly throughout his career.

When a large part of the Thai population, and the international community alike, has become so accustomed, almost to the point of being immune, to these images, the use of clothing to represent them successfully breaks the ice.

Clothes are part of our everyday life and so is fabric. Instinctively, we know what these materials must feel like.

In contrast with the introspective 78, Changing Room relies on the audience's active participation. Viewers are invited to try the jackets and hats on.

In part, this makes for dark, comedic reactions as some participants put on the military gear -- most of them still have the army shop's tag attached to them -- "best quality of battle dress uniform" -- and wander off without a thought, or upload their selfies and mirror portraits on social media.

"The military uniform is a symbol that can draw varied responses from different groups of people," Jakkai said. When seeing it, some react negatively, others on the contrary may feel safe.

The artist has been observing his audience's reactions since the day the exhibition opened. Some people, mostly foreigners, he said, were rather appalled by the behaviour of those who they see as "missing the whole point".

"Others don't like the installation at all and feel that I am taking advantage of a tragic situation," he added. But Jakkai saw today's selfie culture as an opportunity to propagate his message on social media.

"It's true that some people aren't interested in the meaning. They just see an interactive work and play along."

But once these images are present on media platforms, people look at them compulsively and, slowly, viewers begin to register their significance.

Prior to showing his works in Bangkok, Jakkai brought the whole installation set to Patani, where he asked locals to review it. Their response was largely positive, he said.

"As long as their daily ordeal is conveyed to the public, they are satisfied. Otherwise, no one would talk about it."

Finally, the last volet of Jakkai Siributr's exhibition takes us from Thailand's restive south to Myanmar, where another sectarian conflict is raging.

Outlaw's Flag, an elaborate piece which features 21 fictitious flags hanging, addresses the problem of statelessness among the Rohingya people.

The artist paired his installation with a video he shot in Sittwe and Ranong -- both being the departure and arrival points of Rohingya refugees' boat journeys.

While the issue has received far more coverage in the past few years than Thailand's southern insurgency has, Jakkai became interested in it because it also involved a religious divide, although its nature and the stakes are different from the conflict he has previously portrayed.

Furthermore, Thailand has become an integral actor in this high-stake human ping-pong game, when the country refused to take in Rohingya refugees.

"It's not just Thailand," he added. "Bangladesh and Malaysia did the same."

As nationalism is among the root causes of the Rohingya people's statelessness, Jakkai chose to address it using its most prominent symbol: flags.

Drawing his inspiration from the national flags of four countries -- Myanmar, Bangladesh, Thailand and Malaysia -- as well as the Union Jack, due to Britain's colonial past in the region, he proceeded to create a banner for an imaginary country.

In doing so, Jakkai's methodical, diligent research led him to integrate vernacular elements such as the Burmese longyi or Buddhist monk's robes.

In 2015, the artist spent five days in Sittwe, the Rakhine state's capital and, often, the Rohingya people's departure point, before they are left wandering at sea.

"I'm not a journalist. I didn't have access to the refugee camps, so I just wandered around," he said. Noticing broken bits of plastic, glass or animal bones on the beach, as well as remnants of fishing nets, he decided to incorporate them in his work as decorative elements.

Fairly quickly, Jakkai saw the need to create several flags rather than a single one. Although they are meant to unify, most national flags' use of symbols end up excluding ethnic and religious minorities from their representation.

"In reality, the very fact of having a flag is dividing. Flags tell us 'I'm from this country. You're from another country'," he said.

The stories Jakkai Siributr weaves and stitches, rich with everyday life details, are more relevant today than ever.

In the past, the artist admitted he was wary of showing his more political works in Thailand -- mainly out of fear that he would need to censor himself.

"I believed that, as an artist, my goal was to send my message out there -- anywhere," he said.

But today, his views have changed, especially after having been in touch with local communities that have given him the basis for his art works.

"If I don't show it now, in Thailand, how relevant can it be?"

"Displaced: The Politics Of Ethnicity And Religion In The Art Of Jakkai Siributr" is on show at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre until May 13. There will be an artist's talk on Saturday.