'If you look around the world, the best teaching practice is one of organised chaos," said Anthony Bouchier, founder and CEO of Twig World, a UK-based company specialising in educational videos. "You allow students moments of activity and noise, but you also need to be able to sit them down and engage their attention and curiosity. People employing good teaching practices recognise that is the best stimulus and incentive to learning. That's what technology brings them, which is the whole world in their classroom."

Most classrooms are known for their strict, text-based, teacher-centric nature; chaos and technology, however creative, are the last things that come to mind. Bouchier's Twig offers an alternative: this subscription-based video provider focuses on using short, three-minute videos to teach students about various academic subjects, mainly science and maths. The videos are re-edited footage from the BBC's various documentaries and educational programmes, and can be viewed on any web-browser or mobile device.

Twig is now available in over 70 countries, used in over 100,000 schools around the world. In Thailand, Thai publishing company Aksorn has been in partnership with Twig since 2014, and is now offering its subscription-based service to any students, teachers or schools who are interested in the service. Once you purchase a subscription and receive your account, you can login and peruse Twig's catalogue of videos right from any browser, smartphone or tablet. You also have the convenient choice of Thai or English voice-overs and subtitles.

Tawan Theva-Aksorn, CEO of Aksorn Group, said that this alliance with Twig is just part of Aksorn's continuing attempt to transform the traditional silent, orderly Thai classroom into a "classroom of the 21st century", one that nurtures and instills in its students the virtues of creativity, critical thinking and collaboration.

"The current school system isn't sufficiently preparing our children for this new paradigm of professionalism," said Tawan, who believes that a typical Thai classroom, one that relies largely on the oration and remembering of facts and rudimentary concepts, has failed to instill much of the knowledge and attitudes required to be successful in today's working environment.

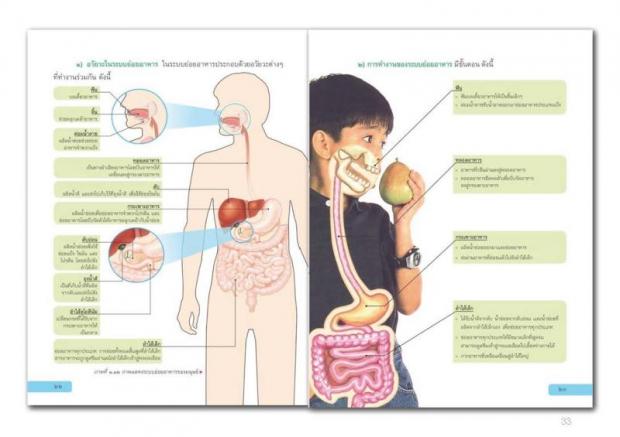

Using high-quality footage and graphical diagrams from documentaries and news reports, Twig videos feel very much like miniaturised documentaries. Twig's video explaining the Yellowstone supervolcano, for example, features voice-overs that concisely explain what the volcano is, its background and its significance. The video is also interlaced with simple graphics that teaches viewers some terms associated with the topic being discussed, such as what geysers, hot-springs or mud pools are, though the topic is still very much focused on Yellowstone. The clip even features brief snippets of interview footage from various scientists to further lend credence to the facts being shown on-screen.

Just last year, Twig saw great success in Malaysia with their science, technology, engineering and maths improvement programme, which used Twig videos to help both students and teachers with their understanding of science.

"All teachers are expected to have a rudimentary ability to teach every subject, be it maths, history or English, as well as a deep understanding of science, and in reality, many teachers struggle," Bouchier said. "If they don't have confidence in their own understanding of science, teachers may not be as willing to allow students to ask questions."

To determine Twig's effectiveness at improving understanding of science, the test compared Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores of children from schools that used Twig and those from schools that didn't.

After the test, aside from a marked improvement in PISA scores, 87% of the students in the sample schools reported better understanding of the science concepts being taught, while all 100% of the teachers from the 52 experiment schools reported improvement in their understanding of both the PISA exam and their science teaching.

"The results were dramatic," he said. "By using videos, we gave students a visual understanding of all the subjects, increasing their confidence in doing science."

Tawan sees technology as another tool that can be used to aid teaching, as children today have become more intimate and proficient with the use of technological interfaces, like smartphones and tablets. Digital resources like Twig as well as other little apps and supplemental materials can help teachers break through the tedium of traditional teaching practices in order to engage their students more, which Tawan hopes will instill in them a curiosity to learn more by themselves.

"If a student wants to learn how a tsunami happens, they can jump on Twig and watch a three-minute video that shows them," he said. "Not only will they have learned about the basic concepts of tectonic plates in a visually engaging way, they'll have also done it on their own, and they can take pride in that. This is the kind of learning ecosystem we want to build."

The topic of education has always been a hotly discussed subject in Thai society. Facing constantly-declining performance scores year after year, most people in society are quick to point the finger at the country's teachers, placing the blame behind the abysmal performance of their children solely on them. This isn't helped by the poor O-Net exam test averages.

"There exists a misconception in Thai society that our teachers are incompetent," said Tawan, who cited the results of a study conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which surveyed students who undertook the standardised PISA exam on whether they felt they were getting sufficient care and attention from the teachers. The results were surprising. Thai students reported feeling as satisfied -- if not more so -- of the attention they receive as their counterparts in top-performing countries around Asia, such as Singapore and South Korea.

Despite that study, the Thai government remains reluctant to give any kind of autonomy to teachers, as most recently evidenced by the junta's decision to restructure regional and provincial educational panels earlier set up by the Office of the Basic Education Commission, giving authority to the various provincial committees instead of the district level. While the junta promises that this centralisation of authority will solve the problem of inefficient and divided management, both Tawan and Bouchier believe the contrary.

"I think the more decentralised and autonomous you are, the more opportunity for quality there is in a way, as teachers who are given more independence will have more opportunities to respond to the specific needs of their students instead of complying to an exam structure," Bouchier commented.

Bouchier believes that instead of having a standardised exam for all students, schools should work with teachers in order to identify the best ways to gauge each type of student, offering varying exams for students with varying talents. For example, artistic students should be tested differently in school from students who are good at systematic thinking. This way, schools can identify the individual talents of their students early on, and tailor their lessons to best develop or appeal to each individual student.

Envisioning the future of education in the country in which each student can learn the subjects tailored to their specific needs outside of class, Bouchier hopes that Twig will be able to serve the needs of personalised or even adaptive learning for children on a one-on-one level. This can probably even serve to help students in the rural areas of Thailand, where good teachers and funding are rarely an option.

"If you sit down a group of teachers and have them tell us the best ways for their students to perform, chances are they already have a pretty good idea of what each of their students are good at. Encouraging children to become apprentices and go into technical education early is a great way to keep students motivated. You can also easily identify the talents and interests of a child much easier this way."