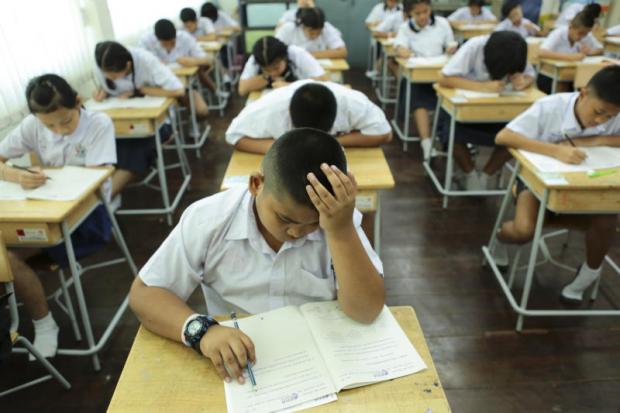

Whose fault is it that our Mathayom 6 (12th grade) students failed four out of five subjects on average in the latest round of the Ordinary National Educational Test (O-Net)? Most scored under 50% in mathematics, English, social studies and general sciences, and just scraped through on the fifth subject, Thai language.

This reflects a nagging problem with Thailand's education system that governments past and present have failed to resolve despite dedicating much of the national budget to the Education Ministry over the years.

In a bid to address this perennial problem, Thammasat University's Faculty of Liberal Arts recently invited two well-known experts from Finland over to share their expertise.

Finland routinely ranks as the world's top global education system and famously has no banding system (all pupils are taught in the same classes, no matter their level of academic ability). It was ranked No.1 in this field by the World Economic Forum last year, followed by Switzerland and Belgium (joint second) and Singapore (No.4).

And as it turns out, the two veterans identified two of the biggest causes of Thailand's educational flaws, and spelled out some ways to fix them.

The main problem is the "inequity" of educational opportunities available for children in urban and rural areas, according to one of the invitees, Pasi Sahlberg.

"If you have a lot of inequalities in your education system, it makes it that much more complicated to increase the quality of education," Mr Sahlberg told the Bangkok Post.

"If you look at the average performance of Thailand in international educational comparison, it proves that the situation is very difficult as long as inequality exists."

Back in the 1970s, when Finland decided to push for major changes to its education system, Mr Sahlberg said his country had a consensual vision that the key to the long-term success of the nation's development was the quality of its human resources -- using enhanced education as an instrument.

This was based on the belief that education has a positive impact on all aspects of a country's development including its economy, politics, arts and culture.

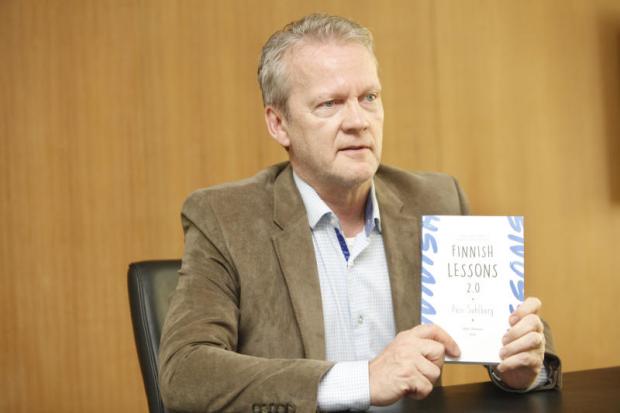

Mr Sahlberg provides insights into the success of the Finnish education, consistently ranked as the world's top global education system. (Photo by Pornprom Satrabhaya)

Since then, Finland has worked to gradually erase inequality by turning education into a public service that is accessible to everyone.

Most Finnish educational institutes are funded by the government, while independent schools, which are operated by the private sector, must be certified by Finnish education authorities to maintain standards.

These practices were designed to do more than just churn out graduates from competitive universities with good grades and good jobs, however. The broader goal was to set a higher standard of general education so that all kids can realise their potential and make a difference to the nation in their own way, Mr Sahlberg said.

Part of this means helping students discover what they are passionate about, and working with parents to channel this passion to constructive ends under a broad national education framework, he said.

Finnish schools have clung to this practice for decades, with the students then able to apply the knowledge obtained in class to their real lives, he added.

He suggested Thai schools allow youngsters to spend more time outside the classroom in "unstructured outdoor play", where they can use and nurture their imagination as well as construct their leadership and collaboration skills.

He also identified a shortage of well-prepared educators as a second major problem hamstringing the nation's efforts. By this he said he was referring to teachers who can recognise and enhance the capabilities of their students.

Making qualified teachers available at each school was also a highlight of the World Bank's recommendations for improving Thailand's education. It also suggested meaningful changes in the school curriculum, criticised by many as too heavy academically for children.

Tiina Malste, a Finnish expert in pedagogical resources, said Finland has always given precedence to improving the performance of its teachers.

Only applicants who score highly in their exams and have a positive attitude toward teaching will be selected for the teacher training programme each year, Ms Malste said, adding that applicants must hold at least a master's degree in education.

In addition, teachers must know how to deal with a diverse range of children, including those with learning difficulties, she said.

During the teacher training programme, the "apprentices" must engage in compulsory fieldwork to gain first-hand experience in the classroom. They must get to grips with how to develop students' learning capacity and self-confidence as well as come up with innovative learning materials.

During this rigorous programme they will acquire new skills and familiarise themselves with what goes into the foundations of a good education, according to Ms Malste.

Furthermore, teachers must broaden their horizons by meeting their peers from different schools to share their experiences, good or bad, she added.

Students of education from several leading universities show their disapproval of an Education Ministry proposal allowing university graduates who do not hold degrees in education to become teachers in public schools and vocational colleges, fearing it will take away jobs from education degree holders. (Pool photo)

In the case of Thailand, Ms Malste said the government should make teaching a competitive career choice for the younger generation. Applicants could then be more rigorously screened with the more highly adaptive and intellectually gifted recruited.

Remuneration and benefits should also be fitting, she said. Teachers should feel they are reasonably paid, respected and have good prospects of long-term employment.

However, both experts warned Thailand not to try and simply emulate the success of other models or countries based on the logic that "one size does not fit all". Some approaches that work in Finland or elsewhere may fail in Thailand due to the different cultural and social contexts, they said.

Thailand should envisage a future direction for its schooling system based on comprehensive research and studies that could shed light on what will work best here, they added.

They suggested that a pilot project could be initiated to fine-tune the country's educational policies and strategies, starting with designated parts of the country. Strengths and shortcomings could be ironed out later.

Local academics agreed with many of their points.

Amornwich Nakornthap, a professor of education at Chulalongkorn University, stressed the need to reduce inequality. He said areas in which Thailand can take cues from Finland are teacher recruitment and teacher development, but that it would be better to have a combination of systems in play.

These could be operated by the public and private sectors due to Thailand's limitations in terms of its bureaucracy and budget, he said.

Mr Amornwich also supported the idea that teachers should at least hold a master's degree in education as this would help broaden their academic insight and understanding of the skills needed to teach well.

Nittaya Arnamnart, who teaches at state-owned Thamai Phun Sawat Rat Nukul High School in Chanthaburi, said many trainee teachers under her supervision have lacked the academic knowledge and experience necessary to even develop a good lesson plan.

Suchada Samutkiri, a teacher at Assumptionsuksa School in Bangkok, said more focus should be put on making sure primary school teachers are well-trained.