In recent years, if you are Thai, you may have encountered an argument about which social class you belong to or how you define others -- probably as a nationalist, liberal, conservative, pro-military, royalist, red or yellow.

If you want to be neutral, some people will let you be, but many will not.

Supachai Kaeokhonyang, 22, has been labelled "an extremist", a categorisation put on him by people who don't know him personally.

He made a documentary about a local community affected by a government-approved gold mine in the Northeast region, but his detractors don't like him because he isn't a conformist "good student" who is supposed to just want to get high grades.

For those who know him, he is an admirer of free speech, humorous, an eager journalism student and an impartial person.

Growing up in an era of both political turmoil and the growth of digital technology, he has encountered a flood of hatred from people, much of it on social media.

Internet users threaten to hunt down individuals for having "no love for the nation", despite vague definitions about what that entails.

Some provoke others by posting images of pork on the Facebook pages of Muslims or ridiculing Lao people and ethnic minorities as "undeveloped" humans.

And that aggression is increasingly travelling from cyberspace to the real world. It's all right to hate somebody if their identity or actions are the opposite of your beliefs.

"People with different opinions become wrongdoers. It seems impossible for us to live together without hatred today," said Mr Supachai, who avoids having discussions about controversial topics to prevent conflict with some friends.

"It only makes me think that we're nearly a robot society. If the first one raises his left arm, others have to go with the left. Whoever is different will be expelled."

Media experts say that the suppression of free speech by the military since the May 2014 coup has inadvertently led to a growth in more rabid hate speech by frustrated people on social media.

CONFLICT MEDIATED

Around 38 million Thais, or 56% of the population, use the internet. A 2016 survey by Thailand's Electronic Transactions Development Agency shows that Thais spend about 6.4 hours per day on the internet.

Over 95% of internet users connect to YouTube, Facebook and Line, a strong indication that social media has a strong influence on consumers.

Social media has been a major stage to express political opinions since the war between the yellow and red shirts flared up a decade ago.

Many Facebook pages were set up to trigger hatred toward rivals, which commonly see hate speech, rape threats, witch-hunts and threats to deport someone out of the country. "The level of hatred [in a society] depends on experience and history, such as the 9/11 attacks that created a wave of anti-Muslim sentiment in the US and globally," said Pirongrong Ramasoota, a lecturer at Chulalongkorn University's faculty of communication arts, which has monitored hate speech on media.

The past decade of political division has expanded the media's reach and influence, with the launch of new satellite TV channels like the yellow shirts' ASTV and the red shirts' People's Channel, as well as corresponding online platforms.

Ms Pirongrong said with the boom of digital media, audiences have greater exposure to incidents that could spark hatred. In past incidents like the Oct 14, 1973, uprising and the Oct 6, 1976, massacre, dissent was swiftly shut down through violence and the seizure of print, TV and radio outlets.

From 2013 to 2014, during the People's Democratic Reform Committee protests, the Blue Sky channel, alongside its websites and Facebook page, delivered news that fomented opposition to then-prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra and her Pheu Thai party. At the height of the PDRC protests in early 2014, the Department of Mental Health conducted a survey of 308 residents in Bangkok and the metropolitan area.

About 59% of participants said that hate speech against political opponents was common. Around 53% said they didn't like aggressive speech intended to provoke hatred, while 25% felt unconcerned about it.

Still, most agreed that the internet is influential, delivering information to 93.8% of survey subjects.

ECHO CHAMBER

Since mid-2014, the military government under Prime Minister Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha has practised censorship, although they have refused to label it as such. Instead, these measures are described as ways to suppress conflict and nurture reconciliation among Thais.

Activities and news outlets that have questioned the legitimacy of the military government have been routinely shut down. This includes an April incident when members of the New Democracy Movement were stopped by police officers for handing out "No" camp pamphlets about the August referendum.

Anti-coup student activists are frequently verbally assaulted by government representatives and internet users for being red shirts and pro-Thaksin Shinawatra, even though they've insisted that they are politically neutral -- only driven by the principles of democracy and equity.

Cyberspace, arguably the last-standing "haven" of free speech, is now being patrolled by the government's Cyber Centre.

More than 900 web addresses carrying "blasphemous" content were blocked by the government between Oct 1 and Oct 31. Twenty-five people were charged with lese majeste in the same time.

A government report shows that 2,308 web addresses deemed likely to provoke conflict and violate the lese majeste law were shut down between Sept 12, 2014, and March 12, 2015.

The military's censorship has received both praise and criticism. While it has helped the government win popularity with some for maintaining peace, others see it as overt suppression of valid dissent. Resistance continues to quietly build against the military.

According to Ms Pirongrong and her team, the prevalence of hate speech across most forms of media declined following the coup in direct response to the censorship measures.

However, hate speech has surged on digital platforms due to restrictions on other outlets.

"When people's opinions are shut down, they'll seek safer spaces to release their opinions. They may feel like they are treated unfairly because one group can speak out while the others are prohibited," said Ms Pirongrong.

"They are likely to seek closed spaces such as social media groups, which will become like echo chambers where like-minded people talk to each other. Hatred is more likely to be generated under these conditions."

In this echo chamber, members will convince themselves that they are righteous as nobody has different opinions, she said.

If hate speech goes unchecked, social tension can reach a tipping point. In 2010, for example, a group of red shirts, encouraged by TV and radio presenters, burned down the Ubon Ratchathani Provincial Office after the Ratchaprasong demonstration in Bangkok was dispersed by the government.

Thailand doesn't have a law to suppress hate speech unlike many European countries, which learned the dangers of such rhetoric with Nazi Germany. But Ms Pirongrong says a law to suppress hate speech in Thailand wouldn't fix the problem.

People are sceptical that a law can be drafted without political interests overshadowing a real consensus on fairness.

"The media itself is not to blame for the prevalence of hatred. The media has a duty to report [hate] incidents. What is to blame is the system that doesn't collaborate to regulate media and allow hate speech to spread," said Ms Pirongrong, referring to broadcasters, politicians and members of civic society.

HATE GONE VIRAL

While online media allows users to connect with like-minded people easily, it fails to bring together different political camps to talk.

Words that directly insult people -- based on their class, gender or ethnicity -- are used in headlines to attract readers and the number of views, likes and shares. A common practice includes mocking criminals' ethnicity or sexuality, with insults ranging from calling someone "brutal Myanmar person" to a "cruel gay".

Media Monitor Thailand, a non-profit organisation focusing on media studies, surveyed four political satellite television channels and six websites in 2012, and found many words of hate are used to devalue, dehumanise and threaten opponents.

Words used to label opponents such as prai (slave), ammart (elite bureaucrats), kwai-dang (likening red shirt supporters to buffalo for being "stupid") and phuak-lom-chao (anti-monarchy) are pervasive on social media.

Hate speech seems to take on a heightened intensity online.

"The media has to ask itself what it wants. Do they want to stir up conflict?" said MMT director Uajit Virojtrairatt.

"It's a challenge for everyone to see media as a tool to enhance themselves and their understanding, rather than to put themselves into the world of media [to get popularity by spreading hatred]."

But it's not just a political issue. Hatred can be generated through random viral events.

On Feb 15, MMT surveyed the television channels, Facebook pages and Twitter accounts run by six media agencies that reported a gathering of a thousand monks and laymen at Phutthamonthon in Nakhon Pathom province. The monks were demanding a prompt endorsement of the 20th Supreme Patriarch.

Pictures and video clips of monks clashing with soldiers went viral on social media. A headline reading "Mob of orange robes" was posted and spread online, making monks not associated with the gathering feel uneasy.

In another study, MMT gathered readers' comments about the Criminal Court's decision to jail news anchor Sorayuth Suthasanajinda for bribing a former employee of state-run media company MCOT. He was found to have fraudulently concealed a 138 million baht fee his firm owed to MCOT.

He was pressured to step down from his morning programme Rueng Lao Chao Nee to take public responsibility, and comply with media ethics.

The survey drew from comments from eight Facebook pages run by digital TV channels from March 1-3. It found that only a few comments about the incident addressed concerns about media ethics. They found 4,776 comments >> >> urging Sorayuth to own up to his actions, while only 660 said he must be concerned about media ethics.

An additional 8,940 comments supported Sorayuth remaining in his job, citing reasons like "he helps others" and "he is smart", and his situation being caused by people who envied him.

Sorayuth's case also spoke to the controversy over the term kon dee or "good people" in society. Generally, it's used to describe decent people, but some argue that this description is often attached to people of a privileged class who can't be criticised by others due to their popularity or status.

A debate about the definition of the term has broken out online.

TEACHING TOLERANCE

Buddhism, a religion that promotes peace and mindfulness, has influenced Thailand for centuries. So why is the country so plagued by hate speech?

A lack of social tolerance plays a big role, said Phra Paisal Visalo, the abbot of Wat Pasukato in Chaiyaphum province.

The rise of fundamentalism, reducing tolerance of social differences, makes people see globalisation as a threat to patriotic concepts of the nation, culture and religion.

"The mainstreaming of globalisation in Thailand over the decades has changed Thai people and how they operate in terms of their career, education, economic status, opinions and beliefs on a whole new scale," Phra Paisal said.

"The economy has increased the income gap, leading to conflict of benefit shares. The Thai political system, which isn't much of a democracy, can't solve these problems. It only worsens them."

Politics is used to serve select demographics at a time, leading people to constantly feel left out.

"What will reduce hate is open-mindedness and tolerance. We must be rational when consuming information. We also need a platform for people with different opinions to have dialogue," he said.

"In the long term, reform of the economic system must be used to reduce the income gap. Reform of the political system, of democracy, and the educational system must further enhance people's tolerance of different politics, religions and cultures."

But less tolerance is not just a phenomenon in Thailand. The prevalence of hatred is also found globally.

According to a recent analysis by San Bernardino researchers in California, anti-Muslim hate crimes reported in the state rose 122% between 2014 and 2015.

Racist language against ethnic Koreans residing in Japan has also grown, prompting the government to pass its first anti-hate speech bill in May.

US president-elect Donald Trump won legions of supporters on a platform of racist rhetoric.

OTHER TRUTHS

Thai activists have striven to diminish ethnic and religious hatred by examining the specific differences behind conflict.

But few have focused on helping people to deal with intense hatred from within.

"When people feel angry or hatred towards each other intensely, it shakes us to the core," said Chanchai Chaisukkosol, a conflict facilitator and a former lecturer at Mahidol University's Institute of Human Rights and Peace Studies.

"It's a feeling of insecurity and doubt. Maybe things they value don't get accepted. They don't connect to each other so they lash out.

"They must build their relationships. I can't see another way out."

Anger proliferates when people's identities are insulted by others.

When they grow defensive and seek to protect their identity, they can be triggered to commit violence, Mr Chanchai said.

Anti-Muslim sentiment in Thailand spread after violence broke out in the southernmost provinces in 2004, three years after 9/11.

In February, a group of locals and monks in Chiang Mai protested against a plan to promote the Halal food industry, arguing it would affect the local tradition and image influenced by Buddhist-Lanna culture.

The building of mosques in Buddhist communities in Nan, Mukdahan and Bung Kan provinces have incited protest, and anti-Muslim Facebook pages have emerged.

Mr Chanchai has sought to solve religious and ethnic conflict by having people of traditionally opposing groups talk to each other. He organised a workshop in the far South that brought together Muslims and Buddhists who expressed a distrust of each other due to the region's history of violence.

He asked them to "step out of their safe zone and tell others about their feelings".

The workshop began with polite conversation, with some saying that they were living together in peace.

"This is true. But there's another truth," Mr Chanchai told Spectrum.

As the conversation unfolded, one Buddhist participant told the others that his friend was threatened by southern violence, and Muslims in the neighbourhood never offered any help or support.

At that point, a Muslim woman broke into tears. "It's not that I don't want to help," she said. "I did help."

The next day, after having extended her support, a bag of rice and some boiled eggs were placed in front of her house, a symbolic act of the southern insurgents suggesting: "Enjoy your last meal before we take your life."

The people in the room reached a moment of understanding.

Hatred is a personal feeling everyone has to deal with in different forms.

According to Nantawat Sitdhiraksa, a psychiatrist at Siriraj Hospital, it is a part of human instinct -- it creates a sense of belonging and influences individuals to assemble in groups.

But that shouldn't stop people from stepping out of their safety zone, from behind the keyboards, to face the truth that it's fine to encounter people who have different views than you.

It takes courage to admit that hatred exists within us and more so, to strive to overcome it.

Media monitor: Pirongrong Ramasoota, a lecturer in journalism at Chulalongkorn University's faculty of communication arts. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

Crackdown: Since mid-2014, Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha has enforced censorship, including making it illegal to campaign for 'No' in the Aug 14 referendum. PHOTO: Thiti Wannamontha

Magic touch: Around 38 million Thais, or 56% of the population, use the internet. Political groups have come to strongly rely on Facebook, YouTube and other online platforms to spread their message. PHOTOS: Patipat Janthong

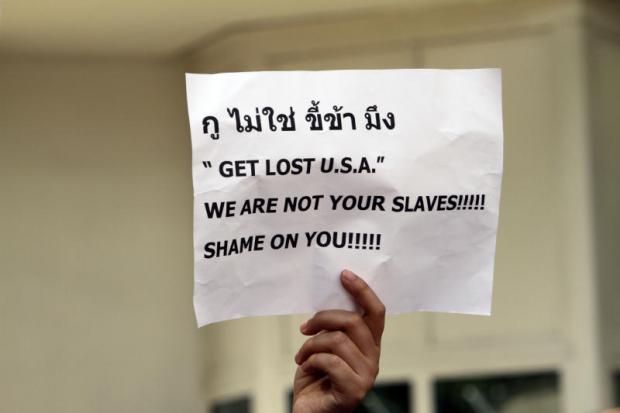

Unwelcome: After accusations of lese majeste were levelled against US ambassador Glyn Davies, protesters gathered at the embassy in Bangkok. PHOTO: Apichart Jinakul