Deep in the jungle in the western border district of Mae Sot, elephants roam with their mahouts in a small village called Ban Pu Ter, long known as the elephant community in Tak province.

Legend has it that Ban Pu Ter is named after Grandpa Ter, the first generation of Karen mahouts who settled in the Thai-Myanmar border village some 200 years ago.

But the sight of elephants could soon be a thing of the past as the number of pachyderms is dwindling fast due to the villagers' changing lifestyle and economic development.

"Twenty years ago, there were 40-50 elephants in our community. Now I think only a couple of dozen remain," says Pinit Bhumwattanangkul, a 29-year-old villager. He adds that a number of mahouts left the village due to the shrinking forest.

Some Karen have sold elephants to earn cash. "Who can blame them? It's getting more difficult to maintain their way of life," he says.

Video by Jetjaras Na Ranong and Jeerawat Na Thalang

The elephant population is threatened by encroaching industrialisation, not to mention development and urbanisation. Tak forest is jeopardised by the special economic zone (SEZ) which has accelerated the need for resources for outside investors. In 2015, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha included Tak among the 10 SEZs slated for development.

The industrialisation of the border province has affected Karen tribal groups who make up 60% of the population of Tak's five border districts -- Mae Ramat, Mae Sot, Phop Phra, Umphang and Tha Song Hong.

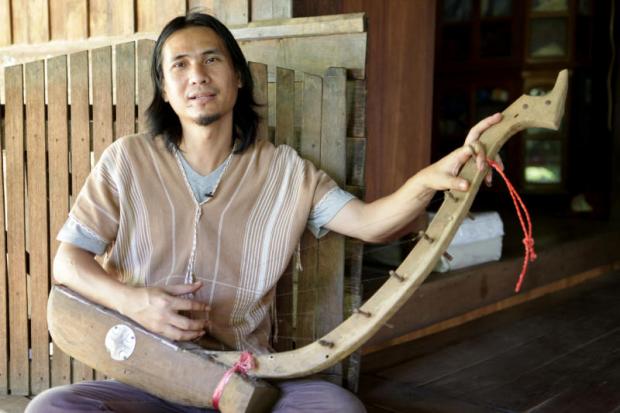

"Karen communities used to thrive by living with the forest, water and earth," says Suwichan Phatthanaphraiwan, a lecturer at Bodhivijjalaya College Srinakarinwirot University, whose ancestors were from the Karen Hermit tribe.

The Karen Hermit tribe, for instance, believe they can gain true wisdom by living in seclusion far from the city. "They grow their hair to symbolise that their commitment to protect the forest will not waver," says Mr Suwichan.

Their ancestors did not have the concept of private property. Community members earned their living in the forest, shared and took care of the quality of their land together.

The indigenous Karen tribes practise rotational farming and use traditional methods to allow time for the trees to flourish. However, such farmers tend to be viewed by forest officials as slash-and-burn renegades who destroy the forest.

Mountains and natural waterways have been an integral part of their life as the Karen believe in environmental wisdom and nature's spirituality.

However, the Prayut government's policy to turn montane watersheds into forest reserves has made it difficult for some Karens to earn a living as they did before. Some 85% of the land in the five districts will become forest reserves, natural parks or wildlife preservation areas, according to a survey by the Thailand Research Fund (TRF).

In the past, a number of Karens have been charged with encroaching the forest. Some were arrested for picking wild mushrooms in the jungle, a custom they follow every June, which is the mushroom season.

Mr Suwichan acknowledged that some Karen people and outsiders were slash-and-burn farmers who destroyed the forest. "That's why we need a strong community which can actively protect our forest with the sense of ownership instead of alienating them," he says.

Otherwise, many Karen have no choice but to shift towards contract farming, even though single-crop planting can degrade the quality of the soil due to the excessive use of chemical fertilisers.

Besides, many are driven into a cycle of debt because they have to buy fertiliser repeatedly to feed the contract farming crops.

According to Tak Agricultural Office, in 2011 here were 73,786 rai of cassava plantations and 679,716 rai of corn plantations. The TRF found that the majority of plantation workers come from neighbouring countries.

The plantations use pesticides which leave chemical residue in the ground.

"It is against the Karen's traditional way of life. But the community does not have much choice now," says Mr Suwichan.

LABOUR REGULATIONS

Karen communities stretch along both sides of the Moei River, a tributary of the Salween.

Following decolonisation, Moei became a demarcation line between Myanmar and Thailand. "But culture and ecology cannot be separated," says Mr Suwichan.

Tak has the highest number of Karen tribes following Chiang Mai, with the majority living in five border districts which have served as a trade gateway for more than a century. Called the West Gate, it connects Thailand with Myanmar, India and China.

With the advent of the Asean Economic Community, land prices shot up in anticipation of the government's plan to construct a transport route from Mae Sot to Mawlamyine and Rangoon in Myanmar, connecting to the Asian Highway to India.

In 2015, the government included three districts of Tak -- Mae Sot, Mae Ramat and Phop Phra -- in the SEZ, providing tax incentives and other perks to attract outside investors, easing foreign labour regulations and improving transport network and infrastructure as part of the East-West Economic Corridor, among other measures.

The government plans to turn a vast area covering more than 5,600 rai in Mae Sot into a logistics and industrial park to connect with Myawaddy in Myanmar. If things go as planned, the development of the industrial park will start next year and become operational in 2019.

Rising land prices along the designated route have prompted many locals to sell their property as their children are less interested in continuing the traditional farming lifestyle. Those who remain in the mountains are vulnerable to the economic interests of outside investors.

Tak these days is bustling with construction. Farmland has been are levelled and covered with soil in preparation for the construction of roads and buildings. The second friendship bridge between Thailand and Myanmar is scheduled to be completed soon. Big superstores are coming to town, while a number of casinos have sprung >> >> up on the Myanmar side of the Moei River. The long-standing cultural heritage of the diverse Karen tribes, who have inhabited the area for at least 200 years, is under threat as the local communities lose their sense of ownership in the community.

"The top-down development does not take into account our social capital. Let's say we have fish in the water, but they bring in ducks and they kill our fish," said Mr Suwichan.

MEDICINAL QUALITY

Phop Phra hot springs has long been a sacred place for Karens who gather there during a special ceremony to seek blessings from nature. When people fall ill, they ask for permission to use the water by performing a ritual offering of betel nut and tobacco to the hot springs before collecting a couple of bottles of water to sprinkle on their bodies, says Yongyoot Natnirandon, a Karen community leader in Phop Phra.

"It shows that we respect the holy water. We would never urinate in the water or put our feet in the water," says the 49-year-old public health worker, who says he believes in the spirituality of the water. He adds that spring water contains sulphur, which has a medicinal quality. Two natural hot springs are located in the soon to be designated natural park area once considered the communal forest. The Forestry Department has turned it into a tourist destination. The department built a small waterway in an outdoor spa to allow tourists dip their feet in the water.

"Karens don't put our feet in the holy water like that," says Mr Yongyoot.

Meanwhile, locals are finding it more difficult to access the third hot spring now that a commercial company uses it as a source of drinking water.

Mont Fleur drinking water, whose facility bears a sign saying that Gen Sunthorn Kongsompong presided over the inauguration ceremony, is located close to the community.

"Sometimes, the entrance to the third hot spring is locked even though it is in a natural park that everyone should have access to. The authorities say they fear local people will pollute the water," says Mr Yongyoot.

NATURAL HABITAT

Ban Pu Ter village, home to some 1,650 people, has been known as the Karen elephant community during the past two centuries.

The village on the Thai-Myanmar border provides a perfect natural habitat for wild animals. Surrounded by shrub, a small waterway in the village is a popular place for mahouts to bring elephants to train and bathe.

On the day of Spectrum's visit, three mahouts brought two adult elephants and a baby elephant to play at the site.

The small jumbo aged less than two years old followed its mother. An 11-year-old lad was riding one of the adult elephants. He has been training to be a mahout for two years.

The well-known Motala, whose survival captivated the nation 18 years ago, also hailed from Ban Pu Ter. The female adult elephant stepped on a landmine in 1999 when it was leased to work in Myanmar. Motala was badly injured and treated at a special elephant medical centre in Umphang.

Today Motala wears a prosthetic leg but it is unable to return to Ban Pu Ter because it cannot walk to its home village. She now lives at the medical centre where she was treated.

Although the accident took place almost two decades ago, villagers still regularly visit Motala because she is regarded like a relative of the villagers. "Last month we went to visit Motala and we cried. She's far from home by herself. We do not blame anyone but ourselves for failing to protect our elephant," says Mr Pinit.

He also said since the government announced the policy to return forest areas nationwide to the state, the forest in Ban Pu Ter is subject to government restrictions as it has become a forest park.

"The national park officers told us we can collect wild plants and mushrooms but we cannot sell them. Still, many people feel unsafe. It's better for the government to declare it a community forest so that every villager can share ownership and take care of the forest," says Mr Pinit.

Mr Suwichan says the province's elephant population is dwindling fast. In 2002, there were about 2,000 elephants in the five districts of Tak, whereas the northeastern province of Surin had only 500.

In 2012, Surin had almost 2,000 elephants thanks to the clear conservation policy in the province. In the same year, the five districts in Tak had fewer than 400 elephants. Some of them were sold and leased.

In addition, some communities along the border are stateless, creating questions about the status of the elephants they raise.

"Some newborn elephants are stateless because the authorities refused to register them as Thai elephants. Some villagers opt for the easy way to earn money by selling their elephants and growing single crops under contract," says Mr Suwichan.

"It would be a shame if there are no elephants left in the village because we failed to protect them. I want the next generation to see what the elephants have done for our ancestors," says Mr Pinit. n

For video, please visit www.bangkokpost.com