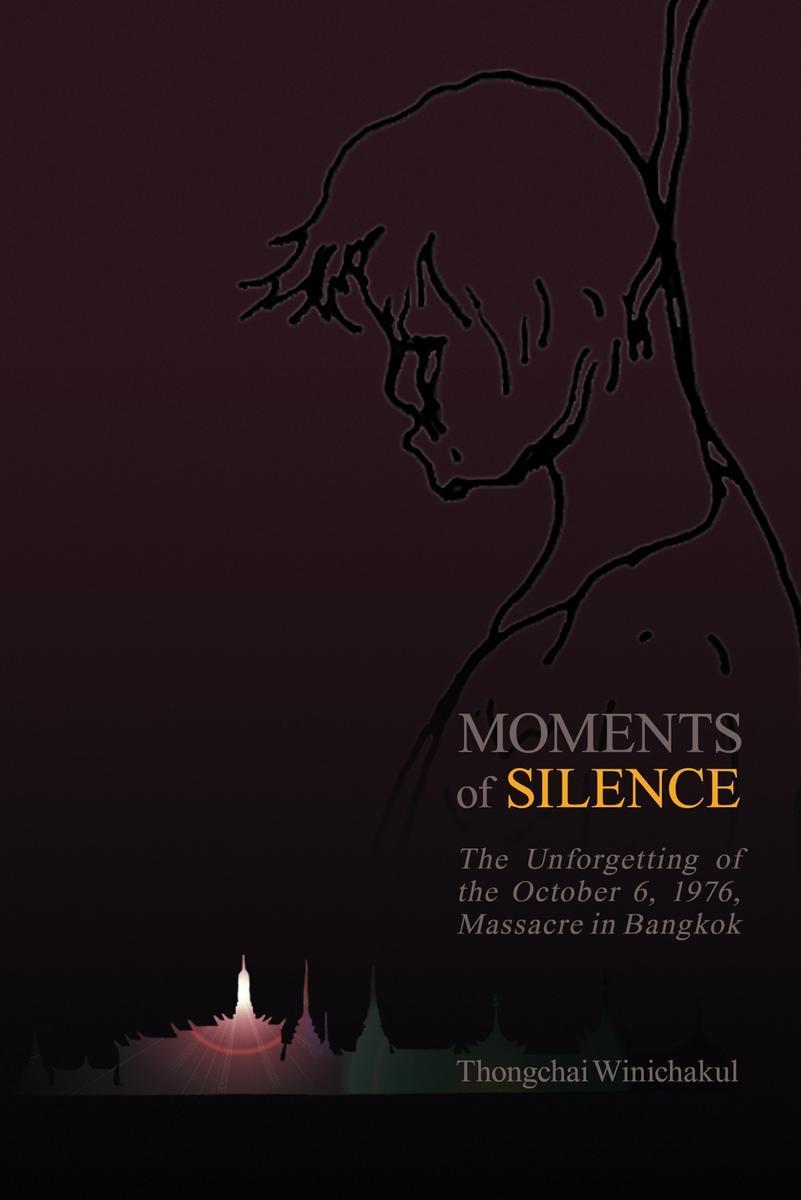

The silhouette at the top right of this achingly beautiful book cover recalls a famous photograph from the Thammasat massacre of Oct 6, 1976. The photo showed a dead man hung from a tree being beaten by a chair while a ring of people watch. The silhouette is deliberately ghostly. The incident is well-known but little known. The photo is famous but the dead man, the man wielding the chair, and the prominent bystanders have never been identified. Even the location of the tree is uncertain. The whole event is full of "unanswered questions". The memory of the incident is in a limbo which Thongchai Winichakul calls "the unforgetting".

Thongchai was holding the mic on stage when rightists assaulted Thammasat University on that day. He pleaded "Please stop shooting" for a long time, watched a good friend die, escaped via the river, was captured nearby, charged with revolt and treason as one of the Bangkok 18, then dramatically amnestied in 1978. For most of the time since then, he has chosen not to live in his homeland. He has become the most internationally celebrated historian Thailand has ever produced.

This book is part memoir, part history, part confession. It is often painful to read and must have been worse to write, but Thongchai says the experience was "fulfilling". The most common adjective is "cruel".

This book is partly about what happened on the day. Thongchai describes his personal experience, and reviews what is known and unknown about who perpetrated the massacre and who suffered. He found the autopsy reports which clarified many mysteries about the identity of the casualties and of the missing. He has read all the memoirs of participants. Most remarkably, in the early 2000s he sought out and interviewed several people responsible for the massacre including police, army, journalists, goons and the radio broadcaster who called out the right-wing on the night before. These accounts shed a little light on the forces that led to the massacre, but not much. Most is still obscured by gloom.

The book is primarily about the memory of the massacre and how this memory has morphed with the passage of time. In the immediate aftermath, the right-wing version dominated. In this version, the security forces had thwarted a movement manipulated by communists and Vietnamese to undermine the nation and the monarchy. After the Cold War faded and this interpretation became untenable, the incident was simply too painful or too dangerous to discuss.

In 1996, in the more liberal atmosphere that also spawned the 1997 constitution, Thongchai proposed a larger commemoration for the 20th anniversary of the event. The proposal clearly touched a chord with other participants. The resulting event brought narrative, photos and footage of the event into public view. The dead were symbolically cremated on the site of the massacre. Some discussion began. The students who had escaped the carnage were at last able to share the pain bottled up for 20 years. It was far from closure, more like an opening to let in a little light.

The 1996 commemoration prompted several attempts to uncover the many mysteries of the day. Thongchai published a widely read article and began the research that expanded the article into this book. Other projects were begun to document the event by archiving memoirs, visuals and other information. These projects were only partly successful because so many of the participants on both sides remained reluctant to unlock their memories.

In the early 2000s, some of the ex-students, now at the peak of their careers, ventured into politics and public life, using their involvement in the 1970s student movement as a credential. The term "Octobrist" was coined. But Thai politics had drastically changed over the interval. The democratic idealism of the 1970s was lost amid new conflicts. The Octobrist camp was split asunder by the Red-Yellow divide. As the mutual vituperation escalated, the idea of an Octobrist politics of idealism was quickly told "to go to bed".

Yet the 1996 revival had nudged enough information on the incident into public view to catch the attention of a new generation. Allusions to the 1976 massacre have been adopted by writers, artists, musicians and filmmakers, usually as signs and metaphors, but sometimes with a blunt literalness. The 2018 hit video of Prathet Ku Mee by Rap Against Dictatorship staged the lyrics blasting the failures of dictatorship against a graphic re-enactment of the famous hanging photograph.

Thongchai argues that the incident is too cruel and too disruptive of the national narrative to be embraced as part of the history, either by the state or by many of its members.

"Silence is a symptom of the inability to remember or forget. I call this condition the 'unforgetting'. "

The resulting disquiet cannot be soothed by a truth and reconciliation commission because those in power want neither truth nor reconciliation. Most of the rightists Thongchai interviewed in the 2000s were unrepentant. Yet the incident cannot be totally erased or silenced either. It is simply so powerful in itself that it makes its own noise. It has a ghostly presence which haunts the present-day, like the book's cover image. In Thongchai's final sentence: "It is within us."

This brilliant book arrives just as a new wave of student protesters has taken to the streets to oppose dictatorship, evidently aware of the parallels between their movement and the 1970s. For these brave men and women, this book can serve as both inspiration and warning. The striking cover, designed by the author's sister, is mostly black except for one point of light, a spire that glows like a candle.

- Moments Of Silence: The Unforgetting Of The October 6, 1976, Massacre In Bangkok

- By Thongchai Winichakul

- Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press 2020

- US$28 paperback

- US$9.99 Kindle on Amazon