Coconuts have been an important economic crop in Thailand for centuries. The farms and plantations that grow them extend over island and mainland landscapes from Surat Thani through Chumpon and Prachuap Khiri Khan, up through Phetchaburi and Samut Songkhram, and every part of the coconut tree has its place in Thai life. It would be impossible to calculate the amount of coconut cream, the subject of last week's column, that is cooked into Thai savoury dishes and desserts every day. Considering these facts it seems incredible that most coconut farmers in the country are impoverished, and that their fortunes seem certain to decline further in the future. But this is the case, in large part because of the way the marketing system is operated by the businesses that control it.

The roots of the problem, however, lie in government agricultural policy, which pays little attention to the well-being of coconut farmers, does not support research into the improvement of coconut tree strains and has put no measures in place to protect coconut trees against the insect that are annihilating them.

Starting on coconut plantations in Surat Thani a pernicious insect has been destroying the palms by eating the buds at the top where new fronds are formed, to the point where almost all of the trees have died in the province. And they are moving northward, having jumped the border to Kui Buri district in Prachuap Khiri Khan province and within a single week destroying every one of the coconut farms there.

Right now the insects are at work on the coconut trees in Sam Roi Yot district, and the next target will certainly be the plantations in Phetchaburi and Samut Songkhram provinces. Once the insects have completed their work, all that will be left of the once luxurious vistas of green coconut palm plantations rustling in the breeze will be long stretches of deformed and dead plants filling a devastated landscape.

Perhaps the government's agricultural-related agencies are just waking up to the fact that it takes a coconut palm 10 years from the time it is planted to produce fruit. Farmers do not get to harvest them overnight, as they do beansprouts.

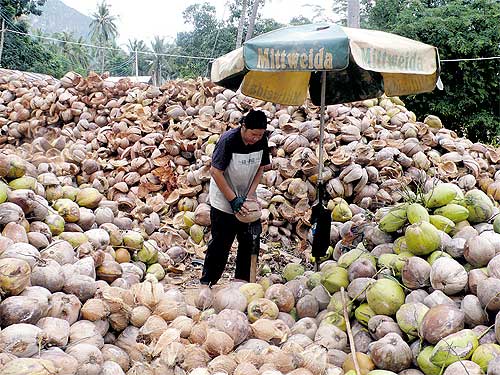

In Sam Roi Yot, groups of coconut farmer villagers collect them to sell to buyers who in turn send them to factories that extract the cream and milk to package as ready-to-use products.

The working procedure of these groups is divided into stages, with a chain of successive duties assigned to different people. Working in shady, peaceful surroundings, the villagers give the impression of being happy and satisfied, but this is far from the case. They are tired and poor, and in great doubt about their future.

Pa, or ''Auntie'', a woman who heads one group, explained that their working system begins with the collection of coconuts from different farms in the area. ''They are gathered by hired workers,'' she said, ''and from there they are given to others who take off the outer husks. Then another group strips the coconuts down to the kala, the hard, brown shell inside. These are broken open and the coconut juice inside is put into bags and the coconut meat is take from the shells. The outside skin has to be scraped off so that the coconut meat is pure white. That's the system we use when we work.''

The factories that process the raw coconut meat into ready-to-use cream packaged in plastic bags or boxes currently pay about seven baht per kilogramme, but the price is not stable. ''It can be lower than that,'' said Pa. ''Once we were paid as much as 40 baht a kilo. The reason we get so much less now is that the trees are being killed off by insects that eat the tops. Not many coconut farms are left, so the government is now allowing the factories to order coconuts from India, Indonesia and Malaysia, and they are much cheaper than the ones grown in Thailand.

''This opens the way for the factories to set a very low price for the coconut meat that they buy in Thailand. And the factories say that if orders for packaged coconut cream on the international market decline, they reduce production and pay less for the coconuts.''

The villagers need two or three coconuts to get one kilogramme of meat. One baht of their income per kilogramme goes to the pickers, and most of the rest goes to those who strip off the husks and hulls, take the meat from the shell and scrape off the skin. It is as if they are supplying the coconut to the factories free of charge, despite their exhausting work and the injuries they sometimes suffer from accidental knife cuts while opening the coconuts and prying out the meat.

In fact, their income comes largely from selling the coconut husks and pieces of shell with the meat stripped off, which has to be dried first, and the coconut juice, which they sell to factories that package it for sale. The earnings for each worker come to less than 300 baht a day, below the government's minimum wage, and the government provides no welfare benefits for coconut farmers.

Also, no one is doing anything to protect the trees from being attacked by insects or to treat the trees that have been attacked. The farmers have to deal with the problem themselves, as best they can.

This is the actual situation for Thailand's coconut farmers. They are very poor and their income from the coconuts they grow is very low, while people who eat coconut or coconut cream in tasty curries and sweets have to buy it ready to use from factories that charge high prices for it. Cooks who buy grated fresh coconut in the market to squeeze their own coconut cream pay a lot, too.

There is a very large gap between the high prices that we pay for coconut products and the tiny amount earned by the farmers who supply the coconuts _ raising questions that are as ugly as they are important.