Embracing the Mae Klong riverbanks, 105km southwest of Bangkok, Ratchaburi province is a cultural must-see that should be known for more than just producing water jars and hosting the Damnoen Saduak Floating Market.

It is important historically and archaeologically for being home to prehistoric humans, and for being part of Dvaravati civilisation during the 7th-11th centuries.

Culturally, Ratchaburi is a place where people of numerous ethnicities have long lived peacefully, conserving their cultures and ways of life. These peoples include the Tai Yuan in Ban Khu Bua of Muang district; the Thai Chinese in Muang, Ban Pong, Photharam and Damnoen Saduak districts; and the Thai Mon in tambon Ban Muang of Ban Pong district.

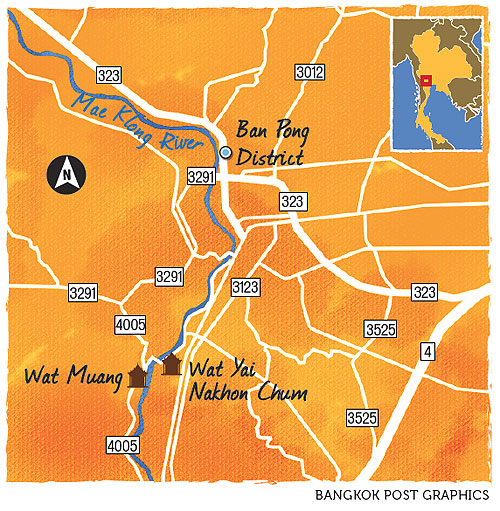

Situated on the west bank of the Mae Klong River in Ban Pong, 80km from Bangkok, Wat Muang is an old Mon temple dating to the Ayutthaya period over 300 years ago, according to a palm-leaf manuscript written in Mon script. It boasts beautiful Mon architecture and art, such as round pagodas and the ordination hall (ubosot) adorned with a pair of swans, a Mon symbol. The principal pagoda is in a shape called chom hae, referring to an outline of a fishnet raised with curved lines at the rims. It is decorated with stucco motifs in the shape of traditional necklaces called sangwal. The lower part of the top, called plong chanai, was painted gold, the peak topped with a royal metal umbrella.

The Wat Muang Folk Museum provides background on the art, culture, religion, education, way of life and knowledge of the Thai Mon in the Ban Muang community, also dating back more than three centuries. It was founded by temple abbot Phra Khru Worathamphithak (Lom Kotchaseni) and local villagers who gathered objects for display there. The objects include thousands of Buddhist scriptures, wrap clothes, pottery, old documents, weapons, religious objects, housewares, farming tools, apparel and kitchenware.

The museum focuses on the simplicity yet meaningfulness of local history, culture and way of life. It depicts the long history of Mon people in the Hanthawaddy period and in the reign of Burma's King Bayinnaung and the nine major migrations of the Mon from Burma to Siam, from the Ayutthaya period until the Thonburi and Rattanakosin periods. The museum is open on Saturdays and Sundays, 9am-4pm. Admission is free.

During Songkran, celebrated here every April 16 to mark Thai New Year, visitors have an opportunity to taste Mon-style khao chae (rice soaked in cool water, often accompanied by supplementary dishes), enjoy Mon performances like phi kradong and saba mon and see simulated local traditions such as the ordination of monks.

On the east side of the river and opposite Wat Muang, Wat Yai Nakhon Chum is located in another Thai Mon community. Thai Mon there have ancestors who had migrated from Hanthawaddy, Burma, to Siam from 1538 to 1541 in the reign of Ayutthaya's King Maha Chakkraphat, and later during the Thonburi and early Rattanakosin periods.

However, there is no evidence to date the establishment of this temple, while locals believe that it was established in the Dvaravati period over 1,000 years ago. According to oral tradition, the Mon immigrants built a new temple on the site of a deserted temple with traces of Dvarati art.

All the temples, including the old ordination hall, pagodas, pavilions and monks' living quarters, and are in the genuine Mon art style. The most important place is Vihara Paki, a hall enshrining the reclining and seated Buddha statues, together with the statues of the Lord Buddha's two closest disciples, Phra Moggallana and Phra Sariputra, before their ordinations. The statues depict Phra Moggallana and Phra Sariputra wearing Mon-style clothes.

The new ubosot, which has wall paintings of the Mon way of life, stands side-by-side with the deteriorating old ubosot, which needs a big restoration. The walkway connecting both halls serves as the venue of the takbat thewo (almsgiving) ceremony held each year on the last day of Buddhist Lent. The ceremony depicts the Lord Buddha descending from heaven to Earth. A Buddha statue is towed from the hall and followed by monks walking from the hall to receive alms from waiting Buddhists.

During Songkran, the villagers set up shrines for the goddess of Songkran in front of their houses and present khao chae to monks at local temples. The Mon's khao chae is different from khao chae based on palace and other recipes incorporating spicy mango salad, salted radish boiled in coconut milk, and sweetened, shredded, dried striped snakehead fish.

At Mon temples, monks chant and pray in the Pali language in the Mon accent. On Buddhist days, the locals make merit by placing a set of food consisting of a bowl of rice, one or two dishes and a kind of dessert at temple canteens, for representatives to present to the monks at sala kan parian (multipurpose pavilions).

During important festivals, Thai Mon like to wear traditional costumes to temple. Men in Ban Muang, mostly the elderly, don a sarong with large chequered patterns, and those living near Wat Yai, mostly young men, wear a sarong with small chequered patterns.